Here is an extract taken from our latest eBook release: The Connell Short to Henrik Ibsen's A Doll's House (now in print format) written by academic Kirsten E Shepherd-Barr.

MYTH 1: Queen Victoria and the Archbishop of Canterbury saw a production of Ghosts as part of her Jubilee celebrations in 1897. It is simply unfathomable that this ever could have happened: why on earth would they go to see a play that had been refused a license by Her Majesty’s government’s own official censor, the Lord Chamberlain? It would be utterly inexplicable. And that is exactly why George Bernard Shaw thought it up – such a deliciously improbable event, so irresistible to imagine, presented in an 1897 article as if it were true.

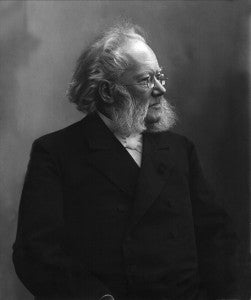

Henrik Ibsen by Gustav Borgen

This bit of Shavian mischief was then incorrectly rendered as fact by Michael Egan in his book Ibsen: The Critical Heritage, a book that is one of the first sources anyone interested in Ibsen turns to. Tore Rem in a recent book on Ibsen (Henry Gibson) corrects the error but it lingers on, a booby-trap for new generations of Ibsen scholars and readers. It is important to correct this “factoid” because it gives a completely false sense of acceptance of Ibsen in England at a time when in fact his plays were still controversial and apt to shock – especially Ghosts, which was not granted a license until 1910.

MYTH 2: Ibsen is only interested in domestic drama. Despite his reputation as a domestic dramatist, Ibsen is not exclusively interested in interiors. Though many of his plays are domestic dramas – A Doll’s House is set entirely inside one house, for example – many of them are strikingly aware of nature and bring it on stage, whether literally or metaphorically. Ghosts, for instance, asks for a huge picture window showing the scene outside: endless rain and a gloomy view of the fjord.

Avalanches occur in three of Ibsen’s plays, and in Peer Gynt the lovely Solveig pursues Peer on skis, an entrance as memorable as that of the vibrant Hilde Wangel hiking onto the stage in her mountain-walking costume and walking stick in The Master Builder. The mermaid-like Ellida in The Lady from the Sea enters dripping wet from swimming in the fjord. Water, snow, mountains, the elements: nature is everywhere, and deeply influences Ibsen’s characters. He was a pioneer in using drama to explore and stage how environment works on character.

(MYTH 3: Ibsen was kicked out of Norway and went into exile. In fact, he opted to live abroad, first in Italy and then in Germany for a total of 27 years until finally returning to Norway in 1891 at the age of 63. Indeed, far from being kicked out of Norway, he received some financial support from his home country during his self-imposed exile. He left to gain wider experience of life and exposure to new ideas, particularly the liberalism of Darwin, Mill, Brandes, and many other thinkers and writers of his time.

1917's adaptation of A Doll's House

MYTH 4: Ibsen is old-fashioned and boring. For many decades of the 20th century there was a mistaken sense of Ibsen being “a fuddy-duddy old realist,” as Toril Moi puts it in her book Henrik Ibsen and the Birth of Modernism. This says a lot about the shortness of memory, because at the time (the late 19th century), realism in drama was revolutionary, and naturalism even more so. As Moi argues, Ibsen’s realism and naturalism have been misunderstood and have led to the assumption that he was only the precursor of modernism and not one of its foremost examples. In the theatre, realism and naturalism were key parts of modernism, not merely forerunners to it, and Moi shows how integral these developments were to what became known as Modernism, particularly in the plays Ibsen wrote from 1880 onwards.

The quintessential modernist, James Joyce, so revered Ibsen that he wrote his first substantial article on the playwright (a review of When We Dead Awaken, Ibsen’s final play) and, more importantly, tried to emulate Ibsen’s work in his own play, Exiles, written around 1915. Other modernist writers lauded Ibsen’s work precisely for its mining of the psychological subconscious, rather than for his realist depictions of bourgeois life; the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke admired Ibsen’s “ever more desperate search for visible correlations of the inwardly seen”, while the Belgian Symbolist dramatist Maurice Maeterlinck sought to emulate what he dubbed Ibsen’s “dialogue of the second degree”, or the implied text beneath the spoken words.