The origin of Mark Twain’s name

Share

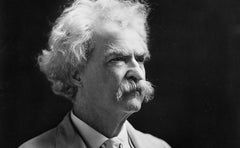

Before “Mark Twain” he was “Thomas Jefferson Snodgrass”. And before “Thomas Jefferson Snodgrass” he was “Sieur Louis de Conte”, “John Snook” and even “Josh”. Samuel Clemens, America’s classic satirist, used a litany of pseudonyms before settling on the name we know him by today. In the latest issue of the Mark Twain Journal Kevin MacDonnell reveals how and when Samuel Clemens decided conclusively to adopt Mark Twain as his pen name.

Up until now there have been a number of competing theories about Clemens’s pseudonym. Most popular is the suggestion that the name derived from the riverboat call, “by the mark, twain”. Twain was an old-fashioned way of saying two, and the call referred to sounding a depth of two fathoms, which was just safe enough for a steamboat travelling down the Mississippi. The problem with this interpretation is that “twain” would have been an uncommon word choice on the Mississippi – MacDonnell’s research shows that Clemens’s own journals from his steamboat days use “mark two” instead of “mark twain”.

Another theory surfaced while the author was still alive. In 1873, The Nevada Sentinel reported that the name came from Clemens’s habit of spending his nights drinking at the Old Corner saloon in Virginia City, a bar that “always had an account with the balance against him” tallied in chalk marks on the wall. Clemens supposedly asked the barman to “mark twain” against his tab so often that the phrase became a nickname.

When Clemens stumbled across this interpretation in a newspaper he decided to settle the issue once and for all by responding in a letter, which reads: “‘Mark Twain’ was the nom de plume of one Captain Isaiah Sellers, who used to write river news over it for the New Orleans Picayune: he died in 1863 and as he could no longer need that signature, I laid violent hands upon it without asking permission of the proprietor's remains. That is the history of the nom de plume I bear.”

MacDonnell, however, argues that this response is only a symptom of Clemens’s notorious tendency to tell tall tales and stretch the truth. MacDonnell’s research led him to discover a sketch that uses the name in 1861, two years before Clemens says he adopted it. The magazine in question was the comedic journal Vanity Fair (unrelated to today’s Vanity Fair) – which Clemens later referred to as an early influence on his work. The sketch depicts a group of Charleston mariners who are “abolishing the use of the magnetic needle, because of its constancy to the north”. The characters involved are named “Mr. Pine Knott”, “Lee Scupper”, and “Mark Twain”.

The three names are nautical puns: the first for dense wood, the second for a drain and the third for shallow depth. Clemens took a liking to the latter, adapted it and invented the Captain Sellers story later in order to promote his burgeoning series of riverboat writings. Though MacDonnell’s theory may undercut Twain’s self-romanticisation, it reveals his cunning in developing an authorial brand. Of all Twain’s tall tales the history of his name may be the tallest.