If Not, Not, 1975, Ronald Brooks Kitaj

Photography by Antonia Reeve

© R. B. Kitaj Estate

£0.00 GBP

By Elsie Hayward

Student Writer

T.S Eliot’s modernist masterpiece The Wasteland was written in the aftermath of a devastating world war. The very fabric of it seems traumatised, being as it is ‘a heap of broken images’, or a series of disconnected, disembodied voices. In the fragmentary feel of the poem, we experience the fragmentary state of the traumatised mind, where snatches of thoughts refuse to make sense together. Yet this is more than just a reference to literal shell-shock - we are being painted a picture of a traumatised society. As Derek Traversi writes in his book on Eliot, The Wasteland is a comment on ‘the state of a civilisation’, although its vehicle is individual scenes and voices. There is nothing else like The Wasteland. It is an announcement in itself that things are not as they were, that the old rules do not apply, the old conventions cannot adequately express the way things are now. We cannot see the world in the same way. Does any of that sound a little like where we are now, in the centenary year of its publication?

If we can think our way back to the start of the first lockdown, it was Spring; around April- time, in fact. It was also one of the most beautiful Springs I’ve known and I remember this making me somehow uncomfortable. It does, after all, feel inappropriate to be ‘breeding lilacs out of the dead land’, or watching nature brazenly come into bloom while we are surrounded by death. How many of us literally did this - tended plants in our gardens while the world was in upheaval, focusing on one little piece of renewal while knowing so much of the rest of the world is ‘dead land’? Perhaps this is the key to one of Eliot’s most puzzled-over lines; the answer to why ‘April is the cruellest month’. ‘Memory and desire’ seems like a formula for hope, where we carry the happiness and comfort we knew and long to know it again. This could be cruel in a world of uncertainty, where we do not know how or if we get out of this, or even if the people in charge do.

Although The Wasteland is a desolate landscape, we feel a connection to it and its rhythms. After all, it is still governed by nature; there is still Spring after Winter, and haven’t we all felt more aware of these changes, and taken a little comfort in their unchanging cycle? Even, that is, if our perceptions and receptions of them are jumbled - if we are ‘warmed’ by Winter like hibernating creatures, and ‘surprised’ to see Summer again, which is so often the most anticipated season. I know I have wondered something along the lines of ‘what branches grow out of this stony rubbish’, and, aside from more literally speaking a lot of people’s vegetable patches, there have been so many different answers; so many different visions of a society rebuilt. We’ve been promised countless lessons, silver-linings, ways that we will do things better: get our priorities straight, be more mindful, chuck out less pollution, work less, love each other more, listen to the birds. I don’t know where Eliot leaves us on this, but I suppose there is an inherent hopefulness in fishing, even if ‘London Bridge is falling down’ just behind, like in a particularly destructive bombing raid.

I think we’ve all had to think more about death over the last couple of years than we have before. It was certainly on Eliot’s mind too, and as we’re watching the ‘crowd’ of dead that ‘flowed’ over London Bridge, like blood from an unstaunchable wound, it’s hard not to be reminded of a constantly increasing Covid death toll. To make matters worse, we overhear someone ask, ‘the corpse you planted last year in your garden, has it begun to sprout?’, which is an uncomfortably literal reminder of the circle of life, as well as a kind of shaming for continuing in the face of the death around us. We can’t ignore the part death plays in the workings of everything anymore. We aren’t sure, but the ‘third who walks always beside you’ may well be the grim reaper, ‘gliding wrapt in a brown mantle, hooded’, a quiet but constant presence. In The Wasteland, nature is against us, just as it is when it throws a virus our way. In the poem, there is attack from the elements, in the form of ‘burning burning burning burning’, and ‘Death by Water’. Both of these are levelling, humbling - we are reminded that the drowned Phlebas ‘was once as handsome and tall as you’. When it comes to suffering, to vulnerability to nature’s nasty tricks, perhaps we are all in it together.

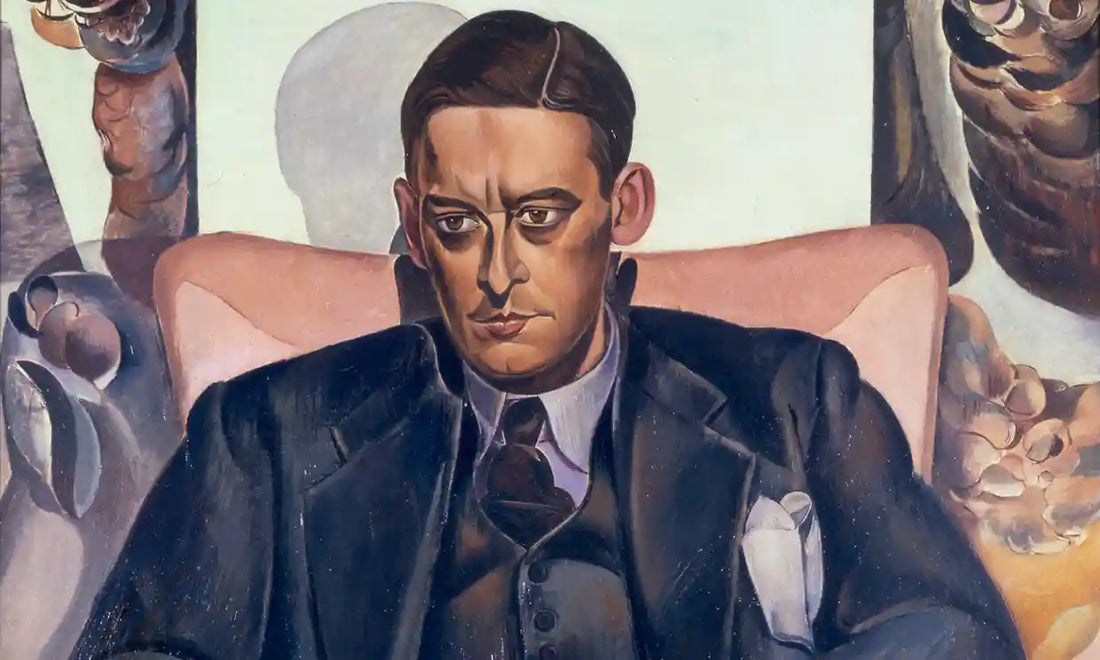

Part of TS Eliot, 1938, Wyndham Lewis. Photograph: The Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust/Bridgeman Images

The Wasteland is not a place characterised by human connection. I’m not sure how well we know how to handle it any more either, as out of practice as we’ve generally been. There is Lil and her husband Albert, separated like many couples have been while he’s away with the army, but their reunion will be an uneasy one. According to their nosy friend at least, their relationship has been reduced to something shallow and superficial, where Albert tells his wife ‘I can’t bear to look at you’ because of the state of her teeth. We haven’t been doing so much looking at each other in recent times perhaps, but we’ve been doing a lot more looking at glossy TV ads and pictures on the internet. Of course, there’s also the awful encounter between the typist and the clerk, which we can now see quite clearly as a depiction of rape, with ‘caresses…undesired’. However, it’s more likely that Eliot was commenting on the way he saw sex being emptied of true meaning, or even love, setting it unromantically in the moment where ‘the meal is ended, she is bored and tired’. Once the transaction is complete, he has no business to stay, so ‘gropes his way, finding the stairs unlit’. Especially now, after several lockdowns, it seems much easier to look for a partner online, and, digital- age love stories aside, this can often lead to something more throw-away, or mechanical. For couples, keeping intimacy following either far too much time together or nowhere near enough must also be a challenge.

Eliot also understands our claustrophobia. You can feel the suffocating restriction of the ‘room enclosed ‘ around the woman at the start The Game of Chess, with the ‘smoke’ and the ‘strange synthetic perfumes’, and the relief of ‘the air that freshened from the window’. Trapped and as good as alone, we also feel her anxiety conveyed in the fragmentary speech that follows, and probably relate to her confession ‘my nerves are bad tonight’. Most moving is her desperate reaching for connection, companionship, comfort; things of which many of us have been starved. She demands ‘speak to me…what are you thinking of’, aching to know that someone is there beside her, living this with her, but her reply, ‘I think we are in the rat’s alley’, is no comfort at all. Then, at the very end of the poem, there is the image of us ‘each in his prison, thinking of the key’, and few of us are now unfamiliar to the sensation of our surroundings becoming a prison to us. Eerily, this is then followed by ‘your heart would have responded gaily, when invited, beating obedient to controlling hands’. Even if we all know lockdowns were necessary, and for the best, there was surprisingly little protest against such a major curtailment of our freedoms. Never have we felt so keenly those ‘controlling hands’, and, I’d like to think mainly because of our care for others, we were indeed ‘obedient’. But maybe this is nothing to how clearly Eliot foresees a city emptied of signs of human life, where ‘the river bears no empty bottles, sandwich wrappers, silk handkerchiefs, cardboard boxes, cigarette ends or other testimony of summer nights’. And just to confirm that this isn’t merely a great city clean-up, and a blessing for the environment, there is ‘the rattle of bones’. Death is still hanging around.

If Not, Not, 1975, Ronald Brooks Kitaj

Photography by Antonia Reeve

© R. B. Kitaj Estate