‘Young and so piteously alone’ - what Charlotte Mew has to say about the mental health crisis

Share

Elsie Hayward

Student writer

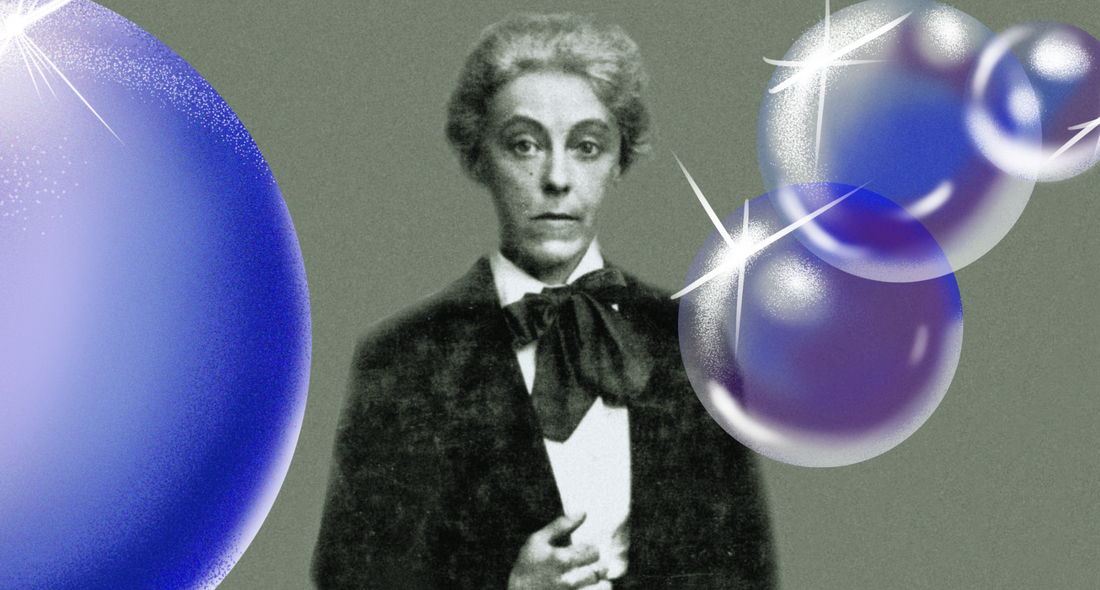

If you don’t know who Charlotte Mew is, don’t worry - most people don’t know her. Also, do worry, because she’s worth it. To give you a brief introduction, she was born in 1869 and wrote from the era of Victorian poetry into Modernism. She was also one of seven children, but only she and her sister Anne escaped early death or commitment to psychiatric institutions. Madness ran in the Mew family, and both sisters chose not to have children to avoid passing it on. When Anne died of cancer, Charlotte fell into despair and killed herself in a nursing home in 1928. She experienced a traumatic childhood, unrequited love for other women, deep family loss, a failure to support herself financially with her writing, and little recognition beyond literary circles. With mental health issues plaguing our society, especially

among the young, does Charlotte Mew have anything to teach us today beyond despair?

‘Sorrow’ is an emotion that Mew explores without fear or restraint. Her Song of Sorrow begins ‘I can sing not of youth or of morning;/ I have ears for no music of bird’, introducing us immediately to a state of being where interaction with the wider world is limited - she can neither use her own voice in this way, nor hear the music around her. This means separation and isolation. All music that could be seen as of symbolic joy, revelry, pleasure, free expression, order and harmony, is robbed from her. All that is left is the uneasy music of sorrow, which hides behind almost nursery-rhyme-like form with rhyme, rhythm and even a refrain of ‘sorrow, sorrow, I sing’, as if to make it more accessible or acceptable. Yet after three opening lines of easy, flowing rhythm, we are brought up short by the line ‘the lives of young lovers’, which does not sit right metrically. Mew is trying, but we get the sense that this feeling is not to be ordered and contained in this way, and the line trails off as if

expression itself is too difficult. Talking about depression is, of course, never easy, and while it would not have been called this in Mew’s time, it is clear that depression is what is being discussed. What else could make us feel we live in a world where no birds sing, one emptied of sensory joy? What else could make us feel so trapped and weighed down that we see no escape, believing of sorrow ‘if it come not today / then - to-morrow’, like a self-appointed prophet of doom?

Yet in reality, Mew is still making music. Crucially, she is still expressing, and this seems to be the best therapy. Above all, she never names a cause for her sorrow. If there is a stigma today about feeling sad for no reason, especially for a lot of the time, Mew does not feel this in her private interactions with the page. She could tell us a tragic life story, but instead leaves it like this - I feel sad because I feel sad, or perhaps, I feel sad because the world is sad, so how could I possibly avoid it - and that is what still speaks to us today. She lets her sorrow be, just sitting with it and acknowledging its existence. Perhaps this is what some therapists would recommend. She comes to discuss sorrow again in a poem simply called Song, this time addressing it like a person, and one with whom she is on familiar terms. Most

movingly, her speaker remembers meeting sorrow as ‘ a little child, afraid to find you at my play’. She does something that we are often afraid to do today, in not reducing or overlooking the feelings of children and young people. By this point, she is also acknowledging a relationship with sadness, seeing it ‘bid and beckon me away’, cast almost in the role of mother. At the same time, sorrow takes the place of a lover as she asks if it ‘was I so dear you could not spare / the maid to love’, and ‘is my bed / so wide and warm that you must lie / upon it’. We’re used to looking at depression as a dark rain cloud, but it might be more fitting and therapeutic to acknowledge it as a kind of companion, however difficult and unwelcome. She touches upon another issue that feels very modern in her

simple confession ‘ I left my love at your behest’, telling us how mental health issues can affect and even destroy relationships. This is also at the core of ‘My Heart is Lame’, whose title also reccurs as its closing line. The image is of a physical fault in the speaker’s heart that means it cannot catch up with the beloved.

Another effect of this overwhelming sorrow is to feel the world around as a hostile or somehow impossible environment. Mew speaks another truth in Song when she describes sorrow ‘always coming unaware’, conjuring the image of an ambush by emotion from around some shady corner. I know that sometimes feelings grip me out of the blue, and it can do little good to try and trace them back to a rational cause. Mew knows this too, and it feels good even to hear it said. The environment is also key in In Nunhead Cemetery, one of Mew’s poems most explicitly about her idea of ‘madness’. Our speaker, the madman in the graveyard, declares ‘there is something horrible about a flower’. It is irrational, and he does not attempt to correct the vagueness of ‘something’, but the world around him conjures feelings in him of unbearable intensity. He is also subverting every prescribed idea about flowers in deeming them ‘horrible’ - not tokens of love, not some of life’s little pleasures, not a pleasant frivolity. Our sense of his uncomfortably “different” perspective is reinforced by his observation in the final stanza that ‘the houses in the street are much too high’, but still there is emotional truth in acknowledging that, especially for those suffering with their mental health, these little things can strike against the heart and mind in a way an outsider might be unable to understand.

<br>

There is also a sense of claustrophobia in his situation that I think speaks especially to the young today. This is picked up in Exspecto Resurrectionem which is written with some bitter irony like a mock prayer. Mew addresses the ‘King’, and asks him ‘dost thou a little love this one/ shut in tonight,/ young and so piteously alone / cold - out of sight?. There is claustrophobia even in ‘shut in tonight’ being literally shut in among white space as a single, short line. This question could not feel more prescient - are those who suffer in a way we cannot see externally really ‘out of sight?’. I know many who have felt that way. For Mew, the emotional struggle becomes physical, as she sees this state as one of imprisonment with the ‘hard and bare’ pillow on the bed, linking the pain on either side of the skull.. There is the

sensation of being closed in by an unfriendly outside world also in ‘Domus Caedet Arborem’, a brief poem written in a quatrain with ABAB rhyme scheme that is reminiscent of some kind of riddle or limerick. It is, however, a single sentence written without a metre giving us a sense of overwhelming panic, and the cause is again ‘houses’, this time ‘dark’ in the night.The speaker feels they are ‘simply biding their time’. To use the terminology of today, I think this is a depiction of some kind of anxiety disorder.

<br>

For Mew, there is sometimes a conscious battle between hope and despair. This is most explicit in The Wind and the Tree, where again she has transplanted the inner struggle onto the outer world, this time putting her own troubled words in the mouth of nature. The wind, ‘mournful’ in voice and perhaps symbolic of the spirit, wishes the sturdy, earthy tree to give in to despair as ‘there is nothing can last or stay’. What it doesn’t realise is that of course the tree already knows this in some respect - ‘the fall that bereaves, /makes the joy of new leaves’. The tree knows a cycle of change, of loss and replenishment, but it also knows that the self is rooted strongly in the ground, however emotional states may change. Mew gives the final world to the wind, who is not consoled as it chooses to see the fallen leaves as symbols of the dead, but the hope has still been planted. There are some Mew poems that

are rather adolescent in their gothic melodrama, like ‘Here Lies a Prisoner’ and ‘Smile Death’, which speak to the macabre instincts of a lot of young people. Yet there is a subtle sensitivity in how Mew calls two of her saddest poems ‘Song’, as if sorrow itself is musical. That would be, I think, a comforting thought to some who live with it closely. It is comforting just to know that she understands, and has already said some of the things we feel are unsayable.